Math Codified - Limits

Prerequisites

- I assume you have a basic understanding of python and math.

- I will be using python 3.6 and above (sorry no legacy code here).

- I recommend writing the code yourself (in a jupyter notebook perhaps) and to play around with it.

- Being prepared for bad jokes

Basics

Limits are a concept in math used in various situations, for example when calculating derivatives. I have a article about how to understand derivatives using python here.

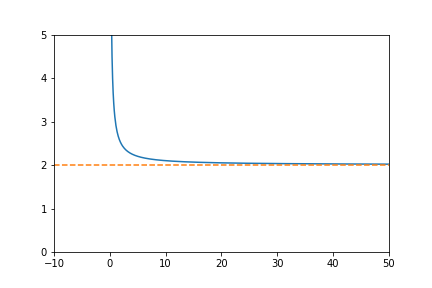

Limits are used when a function \(f(x)\) isn’t defined for a certain input \(x\) or if we want to see if the function has a limit at \(+\infty\) or \(-\infty\) ie if the function converges at infinity (functions can also converge to other functions but that is a matter for another day). That a function converges means that there is a number that the function approaches at \(\infty\), an invisible line it never crosses. Often it can be seen as a “ceiling” or a “floor” like in this picture:

A limit is written as this:

\[\lim_{x \to a} f(x)\]\(\lim\) stands for limes in latin but I always think of it as standing for the english word limit, so if you hear someone talk about limes they are probably talking about limits. \(f(x)\) is the function we want to get the limit of and \(a\) is the limit we want \(x\) to approach. We write \(x \to a\) to say “as \(x\) approaches \(a\)”. The whole expression if spoken would be The limit of \(f(x)\) as \(x\) approaches \(a\).

Can we with that in mind evaluate some limits of the function in the picture above, \(f(x) = \frac{1}{x} + 2\)? Let’s try!

First let’s explore what happens when \(x\) becomes really big, namely when \(x\) approaches infinity. We would write the expression like this:

\[\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{x} + 2\]If we study the graph we can see that the function never seems to go lower than the red-dashed line at \(y=2\), in other words the limit as x approaches \(\infty\) is 2 or as a math expression:

\[\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{x} + 2 = 2\]When you just look at the equation that makes alot of sense as well, \(\frac{1}{x}\) becomes really small when \(x\) is large so it basically becomes \(0 + 2\) at \(\infty\).

A quick note about when to use limits and when not to. If you have a well behaved function (defined everywhere basically) then the limit is just the function evaluated at that point:

\[\lim_{ x \to a } f(x) = f(x)\]It is just when a function isn’t defined for certain \(x\) (or if you want to see how it behaves at \(\infty\)) that limits are useful. We will show this in an code example below.

Exercise

That wasn’t too hard, right? Here comes an exercise for you to test yourself (the answer is at the bottom of this page):

Write a mathematical expression of the limit of \(\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{x} + 2\) as \(x\) approaches \(0\) and write a reasonable answer to that limit.

Code Time!

Now comes the juicy part you came here for! Put on your coding gear, here we GO! (don’t tell me you haven’t got any coding gear, let’s see… I know, take that old hoodie and… a pair of glasses! That looks rather code-ish, right?)

The way we are going to do limits in python is when \(a\) is a number we will add a small number \(h\) to it and evaluate an approximation of the value like this:

# our function. is the same as above

def f(x):

return 1/x + 2

# the small number we will add to x.

h = 1e-3

# The limit as x goes to 0

x = 0 + h

limit = f(x)

print(limit)

# 1002.0

Note: 1e-3 is scientfic notation for \(1 \times 10^{-3}\) and likewise is 7e3 the same as \(7 \times 10^{3}\).

If we test with a smaller \(h\), for example 1e-6, we get 1000002. This is a strong indication that it tends to infinity and if we choose even smaller values for \(h\) the limits get’s higher and higher. We can modify the code to write the answer for multiple values of \(h\) and that could help us see a trend:

def f(x):

return 1/x + 2

x = 0

# a list of the h's we want to test

h_list = [1e-3, 1e-6, 1e-9, 1e-12]

# loop over the h's and evaluate the function at each

for h in h_list:

limit = f(x + h)

print(f"h: {h}, limit: {limit}")

#h: 0.001, limit: 1002.0

#h: 1e-06, limit: 1000002.0

#h: 1e-09, limit: 1000000001.9999999

#h: 1e-12, limit: 1000000000002.0

This is the structure we will be using now when we want to see how a function behaves as it approaches infinity. We will have a list of increasingly big numbers (instead of small):

def f(x):

return 1/x + 2

# list of big numbers

x_list = [1e3, 1e6, 1e9, 1e12]

# loop over the x's and evaluate the function at each

for x in x_list:

limit = f(x)

print(f"x: {x}, limit: {limit}")

#x: 1000.0, limit: 2.001

#x: 1000000.0, limit: 2.000001

#x: 1000000000.0, limit: 2.000000001

#x: 1000000000000.0, limit: 2.000000000001

As we can see it seems to converge to 2 at infinity. If you continue to increase \(x\) you will soon surpass the precision of floating point numbers (that is shown) and it will just display “2.0”. Python is really convinient in the way that you can have really big numbers without worrying about what whether it should be an unsigned, long etc int. It just works! Test to print some really big number, preferably using the notation I have used above if you don’t want to hold the 0-button until the heat-death of the universe. It will handle quite big numbers, numbers to0 big for us to even imagine. 1e100, \(10^{100}\) also called a googol would need to divided by 2 one hundred times just to get down to \(10^{70}\). Think about how big \(2^{100}\) is, even so it is just \(\frac{1}{10^{68}}\) % of a googol. A googol was probably a piece of cake for your computer, then I have a challenge for it: beware! The googolplex ! (the space after the word is to keep the size of the number down, in fact it would be so ridiculously huge that I don’t know how to write it in any other way then that). A googolplex is 10 to the power of a googol, \(10^{10^{100}}\). Seeing as my computer can’t handle numbers larger than 1e300 I have a hard time seeing a computer being able to handle a googolplex without cheating. For anyone interested, a googol is about a googol-th (\(\frac{1}{10^{98}}\)%) of a percent of a googolplex.

If you are reading this at night I apologize for the last paragraph, it might have been a bit to math heavy for this article about codifying math. But I just think that it is remarkable that we can express really big numbers even though we can’t really comprehend them.

That was it for this time, I hope you learnt at least something new and that I haven’t scared you away from math. I would really like to discuss math and such with you so if you are in the mood you can find me on twitter.

Have a nice day!

Answer to Exercise

\[\lim_{ x \to 0 } \frac{1}{x} + 2 = \infty\]An important note here is differentiate between \(\lim_{ x \to 0 } \frac{1}{x} + 2 = \infty\) and \(\frac{1}{0} + 2 = \infty\). The first one is true but the second one is not, this is correct then: \(\frac{1}{0} + 2\) is undefined.

Questions & Contact

If you got any questions comment them below, send me an email or contact me on twitter. The links are in the footer below. You can also contact me there casually just to discuss what’s at the limit of your imagination right now.